Ever wondered how recreational fishing or fishing for sport started?

Well, continue reading this post to get a brief glimpse of its history….

Fishing has been part of the human experience since the earliest stages of human evolution

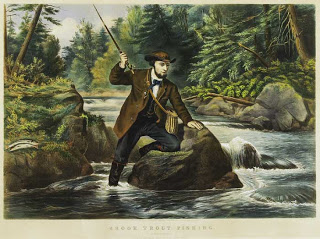

Fishing, also called angling, the sport of catching fish, freshwater or saltwater, typically with rod, line, and hook. Like hunting, fishing originated as a means of providing food for survival. Fishing as a sport, however, is of considerable antiquity. An Egyptian angling scene from about 2000 BCE shows figures fishing with rod and line and with nets. A Chinese account from about the 4th century BCE refers to fishing with a silk line, a hook made from a needle, and a bamboo rod, with cooked rice as bait. References to fishing are also found in ancient Greek, Assyrian, Roman, and Jewish writings.

It is an ancient practice that dates back to at least the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic period about 40,000 years ago. Isotopic analysis of the skeletal remains of Tianyuan man, a 40,000-year-old modern human from eastern Asia, has shown that he regularly consumed freshwater fish. Archaeology features such as shell middens, discarded fish bones, and cave paintings show that sea foods were important for survival and consumed in significant quantities.

The early evolution of fishing as recreation is not clear. For example, there is anecdotal evidence for fly fishing in Japan, however, fly fishing was likely to have been a means of survival, rather than recreation. The earliest English essay on recreational fishing was published in 1496, by Dame Juliana Berners, the prioress of the Benedictine Sopwell Nunnery. The essay was titled Treatyse of Fysshynge wyth an Angle, and included detailed information on fishing waters, the construction of rods and lines, and the use of natural baits and artificial flies.

The history of angling is in large part the history of tackle, as the equipment for fishing is called.

One of humankind’s earliest tools was the predecessor of the fishhook: a gorge—that is, a piece of wood, bone, or stone 1 inch (2.5 cm) or so in length, pointed at both ends and secured off-centre to the line. The gorge was covered with some kind of bait. When a fish swallowed the gorge, a pull on the line wedged it across the gullet of the fish, which could then be pulled in.

With the advent of the use of copper and bronze, a hook was one of the first tools made from metal. This was attached to a hand-operated line made of animal or vegetable material of sufficient strength to hold and land a fish. The practice of attaching the other end of the line to a rod, at first probably a stick or tree branch, made it possible to fish from the bank or shore and even to reach over vegetation bordering the water.

The impact of the Industrial Revolution was first felt in the manufacture of fly lines. Instead of anglers twisting their own lines – a laborious and time-consuming process – the new textile spinning machines allowed for a variety of tapered lines to be easily manufactured and marketed.

For over a thousand years, the fishing rod remained short, not more than a few feet (a metre or so) in length. The earliest references to a longer, jointed rod are from Roman times, about the 4th century CE. As with the earliest rods made from streamside branches, the first longer rods were made of wood, which would continue as the dominant rod material well into the 19th century.

Recreational fishing took a great leap forward after the English Civil War, where a newly found interest in the activity left its mark on the many books and treatises that were written on the subject at the time.

The history of the sport in England began with the printing of Dame Juliana Berners’s A Treatyse of Fysshynge wyth an Angle (1496) as a part of the second edition of The Boke of St. Albans. Berners’s work was evidently based on earlier Continental treatises dating to the 14th century, but virtually no records of these previous writings are known. Many of the methods described in the Treatyse are surprisingly modern and remain in use in some form or another.

Source – Wikipedia, Britannica.com